eLearning is now prevalent across K12, higher education, and corporate learning environments. EdTech companies have provided a multitude of options for these various sectors to select the appropriate presentation method for specific audiences. But not all eLearning platforms are created equal, nor do they all follow any sort of cognitive theory for improving learning based on the challenging user experience of some platforms. EdTech providers and educators alike would serve their customers, i.e. the student/learner, better by considering Richard Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Mayer (2017) combined what we know of information processing theory and cognitive load theory, as well as dual coding theory, and applied it to the use of multimedia in the design of elearning experiences. His combination of these theoretical perspectives can assist teachers and instructional designers in crafting easy-to-digest learning units for students.

Consider these assumptions.

- Learning takes place in an active state whereby learners are filtering information, selecting specific information, organizing it, and then integrating that information with prior knowledge (information processing theory).

- There are two separate channels to process information: auditory & visual (dual-coding theory).

- Each of these channels has a finite capacity for receiving information (Sweller’s cognitive load theory).

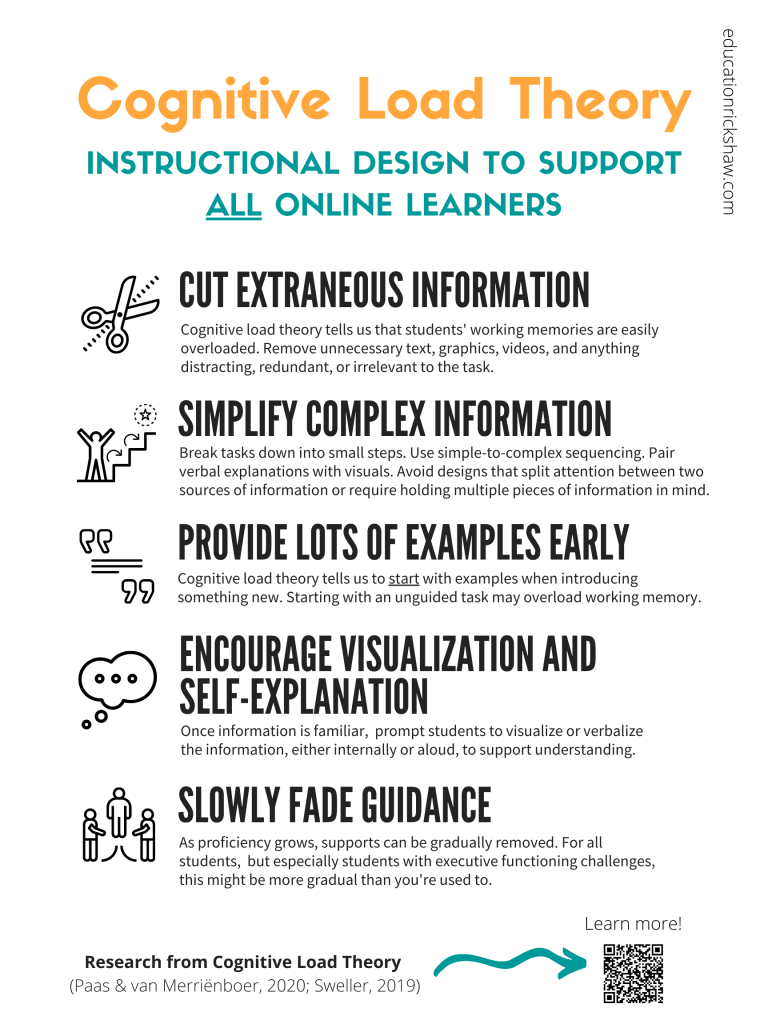

Mayer proposed 12 multimedia instructional principles based off these assumptions as part of his cognitive theory of multimedia learning (Mayer, 2017). These principles are grouped into 3 categories aimed at minimizing extraneous processing (processing needed that is unrelated to the learning objective), managing essential processing (needed to mentally represent the material), and fostering generative processing (making sense of the material). I’ve been working on a training course using Articulate’s Rise360 platform for the last few weeks, and Mayer’s theory resonated with some of the benefits I’ve found in the platform but also brought to light some areas I need to examine in more depth as we consider revisions to the course. More specifically, the three principles that help to foster generative processing (helping learners to organize and integrate new information into working memory) could be used to improve this course.

With a focus on generative processing, the human emotional connection to the material improves. Adding an audio component to several instructional widgets improves the encoding of the information. With several audio elements already part of the course, it’s worth reviewing the tone of the audio recording to ensure a personal approach. The personalization principle (Mayer, 2017) tells us that people learn better from multimedia lessons when words are spoken in a conversational style rather than a formal style. I personally relate to this principle as I prefer a more conversational nature to any video I watch, but never knew there was theory and research behind it. Reading Mayer’s 2017 article in the Journal of Computer Assisted Learning affirmed my decision to start this degree program with UNT — I have always felt that developing an emotional connection to the material helped me to learn and my students in past courses to retain the material better.

Appealing to the nature of being human — the connections between people — helps us be better humans and helps us learn. We are meant to go through life with a community, Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning provides evidence that we still want to feel part of a human community even through elearning experiences…an entire research agenda could be developed off this one statement. The voice principle, whereby people learn better when the narration in multimedia lessons is a friendly human voice rather than a mechanical machine voice (Mayer, 2017), confirms my prior experience as well. I think about how using a Powtoon video to draw or write out examples in the training course while speaking to the examples might help with encoding over just providing a picture of a completed example. Helping learners to organize information into existing schemas, connecting the information to prior learned material — this is where the instruction leads to learning and application.

One final comment on how I might use Mayer’s principles in this training course relate to symbols and imagery. My client is looking to improve the iconography used within the training course to give the material a lasting impression with learners. The course is training individuals on a framework used to organize projects, and the framework contains five phases. Each phase is currently identified using a simple icon. The multimedia principle Mayer explains states that people learn better from words and pictures than just words alone. Adding a word near the icon/image may help with retention of the information in the course. Working with the marketing department or one of the instructional technologists who has experience in graphic design might be a good next step here.

Future Research

Even with lessons designed to reduce extraneous processing and activities focused on simplifying essential processing, tapping into the social element of the learning experience is still critical to get learners motivated to continue learning. Mayer’s generative processing principles dig further into this aspect of learning. Social cues in the lessons help the learner to see the instructor/facilitator as a partner. Using voice instruction in a friendly, conversational tone helps the learner develop a social partnership (Mayer, 2017) which can ultimately lead to better outcomes. We can use on-screen agents to increase the social nature of eLearning experiences. And while Mayer has helped get us started, there is vast opportunity for additional research in the application of the lab-designed principles he has postulated. Examining the role of motivation in multimedia learning is an area of interest for me. I need to look further into Moreno’s cognitive affective theory of learning with media.

Until next time, thanks for learning and reflecting with me.

References

Mayer, R. E. (2017). Using multimedia for e-learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 33(5), 403–423. https://doi-org.libproxy.library.unt.edu/10.1111/jcal.12197